|

Gyps coprotheres (Cape

vulture)

KransaasvoŽl [Afrikaans]; Ixhalanga [Xhosa]; iNqe [Zulu];

Ekuvi (generic term for vulture) [Kwangali]; Lenong, Letlaka [South

Sotho]; Khoti, Mavalanga [Tsonga]; Diswaane, LenŰng [Tswana]; Kaapse gier

[Dutch]; Vautour chassefiente [French]; Kapgeier [German]; Grifo do Cabo

[Portuguese]

Life

> Eukaryotes >

Opisthokonta

> Metazoa (animals) >

Bilateria >

Deuterostomia > Chordata >

Craniata > Vertebrata (vertebrates) > Gnathostomata (jawed

vertebrates) > Teleostomi (teleost fish) > Osteichthyes (bony fish) > Class:

Sarcopterygii (lobe-finned

fish) > Stegocephalia (terrestrial

vertebrates) > Tetrapoda

(four-legged vertebrates) > Reptiliomorpha > Amniota >

Reptilia (reptiles) >

Romeriida > Diapsida > Archosauromorpha > Archosauria >

Dinosauria

(dinosaurs) > Saurischia > Theropoda (bipedal predatory dinosaurs) >

Coelurosauria > Maniraptora > Aves

(birds) > Order: Falconiformes

> Family: Accipitridae

> Genus: Gyps

Distribution and habitat

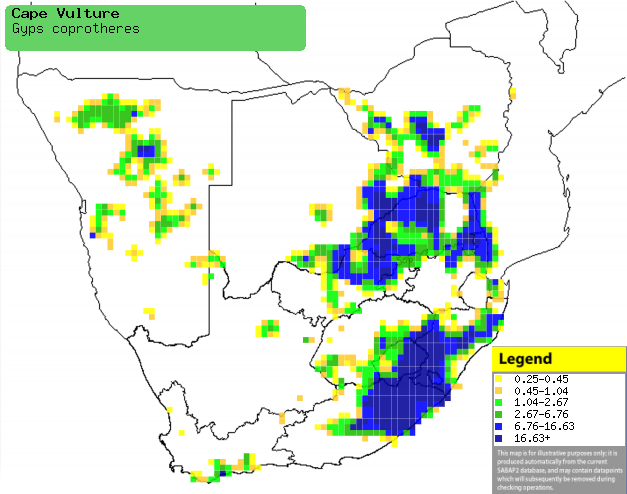

Near-endemic to southern Africa, occurring in patches of Namibia, southern Zimbabwe, Lesotho

and north-eastern and south-eastern South Africa, with a localised population in

the Western Cape; it is a rare vagrant to Angola. It can occupy a variety of habitat types, although it

especially favours subsistence farming communal grazing areas, where there is plenty of

livestock to feed on.

|

|

|

Distribution of Cape vulture in southern Africa,

based on statistical smoothing of the records from first SA Bird Atlas

Project (©

Animal Demography unit, University of

Cape Town; smoothing by Birgit Erni and Francesca Little). Colours range

from dark blue (most common) through to yellow (least common).

See here for the latest distribution

from the SABAP2. |

Predators and parasites

Its eggs are eaten by Papio ursinus (Chacma baboon),

and the chicks are prey of Aquila verreauxii (Verreauxs'

eagle).

Movements and migrations

Resident and partially nomadic, as adults may

travel up to about 750 km from their colony in the non-breeding

season.

Food

It eats carrion, searching aerially for a carcass to feed

on; once on the scene it is dominant over almost all other vultures, except the

larger Lappet-faced vulture. It slices

off flesh with the sharp edge of its bill, eating some of it and storing more in it's

crop, which can sustain it for about three days.

|

|

A Black-jackal challenges a Cape vulture for a

piece of meat, Giant's Castle, South Africa. [photo Johann Grobbelaar

©] |

|

|

The vulture bites the jackal on the nose, which

causes it to retreat. [photo Johann Grobbelaar

©] |

Breeding

- Monogamous colonial nester, breeding in colonies of up to about 1000

breeding pairs, each separated by roughly 2.5 metres.

- The nest is mainly built by the female, consisting of a bulky platform

of sticks, twigs and dry grass, with a shallow cup in the centre lined with

smaller sticks and grass. It is typically placed on a cliff ledge, often

using the same site over multiple breeding seasons.

- Egg-laying season is from May-June.

- It usually lays a single egg (rarely two), which is incubated by both

sexes for about 55-59 days.

- The chick is brooded constantly for the first 72 days of its life, while

both parents feed it on meat and bone fragments for calcium. It eventually

leave the nest at about 125-171 days old, becoming fully independent about

15-221 days later; the fledgling is always chased off the territory by its parents at

the start of the following egg-laying season.

Threats

Vulnerable globally, Regionally extinct in

Swaziland and Critically Endangered in Namibia; its global population has

decreased from roughly 3460 breeding pairs in 1980 to about 2950 pairs in 2000.

This is thought to have been caused largely by habitat loss, persecution for use

in traditional medicine, human disturbance of colonies, poisoning and

improvements in animal husbandry, which result in a decreased availability of

carrion.

References

-

Hockey PAR, Dean WRJ and Ryan PG 2005. Roberts

- Birds of southern Africa, VIIth ed. The Trustees of the John Voelcker

Bird Book Fund, Cape Town.

|