|

Biology of Mantodea

Life >

Eukaryotes >

Opisthokonta >

Metazoa (animals) > Bilateria > Ecdysozoa > Panarthropoda > Tritocerebra >

Arthopoda > Mandibulata > Atelocerata > Panhexapoda >

Hexapoda

> Insecta

(insects) >

Dictyoptera

> Mantodea (mantids)

Body structure

Their head is triangular and extraordinarily mobile with large

compound eyes set very high on the upper corners and three simple eyes called ocelli on top of the head (between the compound eyes). Females

are normally unwinged with the males being winged in order to fly in search of

females. Mantids have long spiny front legs which enable them to aptly

capture live prey.

|

|

|

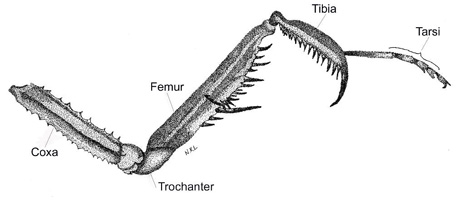

Preying Mantis leg. [drawing by Nicole

Larsen, © used with permission.] |

Courtship and mating

Female mantids are notorious for making a meal of their mates. As her

suitor perches on her back, devotedly doing his duty, she will usually

look round and casually start chewing his head off. Numerous

publications seem to find this snippet of information incorrect.

Unfortunately, we do not really know what happens. Death by

cephalic self-sacrifice certainly seems to be the occasional fate

befalling mating male mantids. This probably occurs when something

goes wrong or disrupts the mating process. It is in the male

mantid's best interest to sire as many offspring as possible so rank

promiscuity with as many females as possible is a highly desirable

objective. Losing his head to his first mate will not help spread

the genes around and the male mantid is equipped with a set of tactics

that help him increase his chances of continued survival during intimate

contact with a female.

Male mantids are shorter and a lot

slimmer than the females, who sometimes look so different that one

is inclined to think they are a different species. This very

possibly puts the males at risk of being bullied with eventual

decapitation by their larger partners. However, during mating, the

head of the male is placed far back on the female so that the phrase

"out of sight, out of mind" might just be the most important factor for

his survival.

The pheremone of the female is so strong that it attracts

a large number of males who then have to fight to gain their prize.

When confronted with one another for the first time, the male and female

mantid fix one another with the typical mantid icy gaze. The male

then carefully and slowly "stalks" the female, this procedure being

carried out for an hour or two. Half-way through this, he launches

into an abdomen-waving sequence then suddenly leaps onto the female's

back (or into her arms if he misjudges). Once he is in position he

bends his abdomen in a motion that is akin to stroking, searching

contact with the females genital area. Finally, he twists his abdomen to

one side and the copulatory position is established. All this

effort does not go wasted, the female responds with pumping movements of

her abdomen and she may raise her fully extended forelegs in the air or

she may approach the male and stroke his front legs. She thus

seems to be an active and obliging participant in the whole mating drama

so the alluring prospect of recasting the partner's part from mate to

meal does not seem to figure. Mating can also be done successfully

without this sequence but success seems to be much higher when the

female becomes actively involved.

Egg laying and development

A female mantid, after a single act of mating, can lay more than one batch of

eggs with sufficient stored sperm. The smallest single egg-batch

known is around ten while some of the larger mantids can lay 400 eggs at

a single sitting. Some female mantids lay their eggs in soil while

the majority attach them to some object, sometimes in conspicuous

places. The eggs are not just dumped in any old fashion but carefully

placed inside a weather-proof protective enclosure, this structure being

called an ootheca. The ootheca is an amazing frothy structure in which

cells are made and the eggs are then deposited into these cells. When

the female has completed her egg laying, the froth hardens and cocoons

the eggs to help protect them from enemies and the drying effects of the

sun. After completing the lengthy process, the female may spend a

few minutes grooming the tip of her abdomen. It is important that

she does this as some froth may remain which would harden and

contaminate the body if not removed immediately.

After about a month, tiny nymphs start emerging from the ootheca via the

net-work of exit holes situated on the upper midline. Upon

emerging from their cell in the ootheca, each nymph is encased in a

membrane. When half-way out of the cell, the nymph pauses, waiting

for the pressure of blood pumped into its head to split open the

membrane, enabling the nymph to then shrug off the membrane. The nymphs

usually assemble on the ootheca, do one or two moults and start

resembling their parents. In some species the nymphs dangle

from a line of silken thread, moult and then drop to the ground and

disperse. One noticeable aspect of a nymph is that it carries its abdomen curled upwards over its back in a semi-circle, a strange

posture for which there is no explanation.

|

|

|

Frothy ootheca being laid. This hardens and

turns a biscuit colour. |

Ootheca

from which nymphs have emerged.

|

Prey and prey capture

Mantids are diurnal

(day active) and have fierce predatory habits. They are well equipped to

carry out their deadly ambush in that their front legs are liberally furnished

with rows of spines. The spines on the femur are slightly tilted in one

direction, those on the tibia in another direction so that when the two sections

are snapped shut the prey is spiked on a kind of mobile gin-trap - no escape.

The long spines on the outermost part of the tibia also act as grappling hooks

as they are slung outwards over the prey's body. It is rare that anything

escapes a mantids grasp. If suitably sized prey comes into view, the mantid

slowly turns its head to view the prey and weigh up the possibilities. As

soon as the mantid has judged the distance to the prey, the front legs are thrust

forwards, moving as fast as lightening. The whole capture is performed

with extreme precision and it is rare that prey escapes the grasp. A mantid can

strike in whichever direction its head is pointing. They are not fussy

eaters and will happily munch away at anything that comes their way, even insects

that share their predatory habits, such as assassin bugs and wasps.

When a mantid begins a meal, it starts with the head or neck, thus cutting

out any means of struggle from its victim. This may be an important

factor, especially when the prey is bigger than the mantid itself. Guillotining

the head also makes way for the juicier parts - the nourishing tissues that are

packed inside the thorax. Mantids are thrifty eaters and normally manage

even the tough legs and head parts, their jaws chewing away from side to side,

processing the food into tiny morsels that will pass down through their rather

narrow gullets. A mantids menu consists of moths, butterflies, grasshoppers,

flies, beetles,

caterpillars and even spiders. They will also eat other mantids which makes that

seem a little bit cannibalistic but when you are hungry and food is scarce,

well.....

Where they live

Mantids enjoy a wide distribution all around the world

except in regions that are permanently cold and they can be found in virtually

any kind of habitat, from the wind-swept seashore to the humid green forests,

from parched hot deserts to chilly mountainsides. Each genus and species is

adapted to the ecological factors of tits residence. In other words, a mantid

that dwells in desert regions would not thrive and succeed if taken from there

and put into a forestry region or vice versa. Children often ask if they

are able to keep a praying mantis as a pet. Yes, you probably could but take

into consideration that mantids wander. A large cage made out of small mesh

wire and a few plants should suffice. And, of course, you have to remember

to catch prey for them otherwise they, in all likelihood, will not survive.

This works by trial and error, one might be successful and then one might not.

Perhaps it is better to leave them where they belong in nature and admire them from a

distance.

Page by Dawn Larsen |